Using a formal property file to verify an AXI-lite peripheral

|

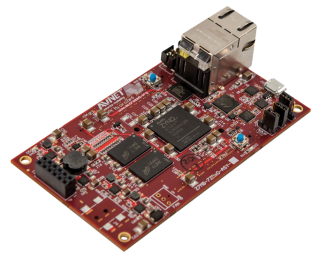

The AXI bus has become prominent as a defacto standard for working with either Xilinx or Intel supplied IP cores. This common standard is intended to make it easy to interface a design to one of a variety of System on a Chip cores, such as Xilinx’s MicroBlaze or Intel’s NiosII. The bus is also used by ARM, and so it is a natural fit for both Zynq and Soc+FPGA products.

While this is all well and good, AXI is a beast to work with. Achieving both correct performance, as well as high speed performance, can be a challenge. Today, we’ll limit ourselves to the AXI-lite bus: a version of AXI that supports neither bursts, nor locking, nor transaction ID’s, nor varying quality of service guarantees. While I’d like to imagine that these simplifications have made it easy enough for a beginner to be able to work with it, I would have to imagine that most beginners who have tried to work with the AXI-lite protocol used by either the Zynq or Soc+FPGA chips haven’t found it to be the simple protocol they were hoping for.

It has certainly been anything but simple for me.

Today, let’s take a look at how you can use a set of formal properties to work with an AXI-lite slave–both to verify that it works as well as to query how well it works. Along the way, I’ll demonstrate how easy it us to use this set of formal properties to find the problems in an AXI-lite slave implementation.

The AXI-lite Bus

Some time ago, I wrote an article describing how to build a simple wishbone peripheral.A simple wishbone peripheral only needed to respond to a request,

always @(posedge i_clk)

if ((i_wb_stb)&&(!o_wb_stall)&&(i_wb_we))

some_data[i_wb_addr] <= i_wb_data;an acknowledgment,

always @(posedge i_clk)

o_wb_ack <= (!i_reset)&&(i_wb_stb)&&(!o_wb_stall);some returned data,

always @(posedge i_clk)

o_wb_data <= some_data[i_wb_addr];and a (never) stall signal.

assign o_wb_stall = 1'b0;Voila! That’s all the signaling required for a basic Wishbone peripheral.

If only AXI were as easy.

|

Instead of one read-write request channel, and one acknowledgment-response channel, AXI has five such channels. For writing values to the bus, there’s the write address channel, the write data channel, and the write response channel. For reading values from the bus, there’s a read address-request channel and a read response channel.

For today, let’s just discuss the AXI-lite version of this interface. Unlike the full AXI specification, AXI-lite removes a lot of capability from this interaction. Perhaps the biggest differences are that, with AXI-lite, any read and write request can only reference one piece of data at a time, and that there is no need to provide unique identifiers for each transaction. There are other more minor differences as well. AXI-lite has no requirement to implement locking, quality of service, or any cache protocols. Once these differences are accounted for, AXI-lite becomes almost as easy to verify as a Wishbone (WB) transaction.

Don’t get me wrong, building an AXI-lite peripheral is still a challenge, but verifying an AXI-lite peripheral? Not so much.

The key to these transactions are the various *READY and *VALID signals.

*VALID is used to signal a valid request or acknowledgment. The two

signals together form a

handshake.

One side of the channel will set a

valid signal when it has information to send, whether request or

acknowledgment, while the other side controls a ready signal. You

may recognize this from our prior discussion of the simple handshake method

of pipeline control.

The AXI specification

also contains a very specific requirement: asserting the

valid signal can never be dependent upon the ready signal for the same

channel.

Perhaps you may remember with the

WB specification

that it takes a hand shake to make a bus request. Both STB

(from the master) and !STALL (from the slave) must be true in order for a

request to be accepted. The same is basically true of

AXI only the names have changed:

*VALID and *READY must be true for a bus request to be accepted by the

slave. This *VALID signal is similar to the

WB

STB signal, while *READY is similar to the !STALL signal.

However, unlike

WB,

AXI

has separate channels for reading and writing, and each of these channels

has its own VALID and READY signal set.

AXI also requires a VALID and READY

handshake

on acknowledgments, both for read and separately for write acknowledgments.

AXI-lite Read

Perhaps it might make sense to walk through an example or two. Fig. 2

therefore shows several example

AXI-lite

read transactions from the perspective of

the slave.

In this example, I’ve chosen to use Xilinx’s

convention where the

AXI

signals are in all capitals, although this loses the i_* and o_* prefix

that I enjoy using to indicate which signals are inputs and which are outputs.

(We’ll switch back later, when we get to the

formal property set.)

|

Each request starts with the

AXI-lite

master raising the S_AXI_ARVALID signal,

signaling that it wants to initiate a read transaction. Together with the

S_AXI_ARVALID signal, the master will also place the address of the desired

read on the bus.

The slave

will respond to this request by raising the S_AXI_ARREADY signal,

although

the specification

sets forth several comments about this. For example, the slave can

set S_AXI_ARREADY before or in response to the

S_AXI_ARVALID signal. Further, all the

AXI

outputs are not allowed to be dependent combinatorially on the inputs,

but must instead be registered.

Beyond that, the slave can stall the bus as required by the implementation.

A read transaction request takes place when both

S_AXI_ARVALID and S_AXI_ARREADY are true on the same clock.

Looking back at Fig 2, you can see four such read transaction requests being made.

As with the transaction requests, the acknowledgments also only take place when

S_AXI_RVALID and S_AXI_RREADY, the signals from the acknowledgment channel,

are both true. Because responses must be registered, the earliest the slave

can acknowledge a signal is on the clock following the request.

Let’s now turn our attention to the acknowledgments shown in Fig 2. In

this example,

the slave

acknowledge the request on the clock after the request is made. Since

the master holds S_AXI_RREADY high, the acknowledgment only needs to be high

for one transaction. Further, in addition to S_AXI_RVALID,

the slave

will also set S_AXI_RDATA, the result of the read, and S_AXI_RRESP, an

indicator of any potential error conditions. As with the S_AXI_ARADDR

signal above, these two signals are part of the acknowledgment transaction

as well.

The more interesting transaction may be the high speed transaction shown at the end of the trace in Fig 2. Judging from this transaction, if the master wishes to transmit at its fastest speed, this particular core will only ever support a rate of one request every other clock.

Working from the spec, just a couple of formal verification properties will help keep us from running into problems. From what we’ve learned examining the figures above, the following basic properties would seem prudent.

-

Once

S_AXI_ARVALIDis raised, it must remain high untilS_AXI_ARVALID && S_AXI_ARREADY -

While

S_AXI_ARVALIDis true but the slave hasn’t yet raisedS_AXI_ARREADY,S_AXI_ARADDRmust remain constant. -

Similarly, once the

S_AXI_RVALIDreply acknowledgment request is raised, it must also remain high untilS_AXI_RVALID && S_AXI_RREADYare both true. -

As with the read address channel, while

S_AXI_RVALIDis true and the master has yet to raiseS_AXI_RREADY, bothS_AXI_RDATAandS_AXI_RRESPmust remain constant. -

For every request with

S_AXI_ARVALID && S_AXI_ARREADY, there must follow one clock period sometime later whereS_AXI_RVALID && S_AXI_RREADY.Unlike our development of the WB properties, there is no bus abort capability in the AXI bus protocol. As a result, following a bus error, you’ll still need to deal with any remaining acknowledgments.

-

Just to keep things moving, we’ll also want to insist that after some implementation defined minimum number of clock ticks waiting the slave must raise

S_AXI_ARREADY. -

The same applies to the reverse link: the master should not be allowed to hold

S_AXI_RREADYlow indefinitely whileS_AXI_RVALIDis high.

We’ll add a couple more properties beyond these below, but for now these should suffice to capture most of what AXI-lite requires.

That’s how reads work, so let’s now go on and examine the write path.

AXI-lite Write Example

While the AXI read channel above may appear to be straightforward, the write channel is anything but. The write address channel is designed to allow a single “burst” request to indicate a desire to write to multiple addresses, closely followed by a burst of data on the write data channel. AXI-lite, unlike the full AXI protocol, has no burst write support. Every address request must be accompanied by a single piece of associated write data. To make matters worse, the two channels are only loosely synchronized, forcing the slave to synchronize to them internally.

Were S_AXI_AWVALID tied to S_AXI_WVALID, and S_AXI_AWREADY tied to

S_AXI_WREADY, the slave’s write channel logic would collapse into the basic

read problem discussed above. Alas, this is not so. The

AXI-lite

slave is thus forced to try to synchronize these two channels in order to

make sense of the transaction.

Fig. 3 shows a basic set of write transactions illustrating this problem.

|

The first three transactions within Fig. 3 shows the bounds set on the synchronization of the channels. Note that I found these bounds within Xilinx’s documentation. They are not present in the specification itself, as far as I can tell. Since they simplify the problem significantly, I’ve chosen to implement them as part of this property set.

Let’s look at and discuss each of the transactions shown in Fig. 3 above.

-

The first transaction is as simple as one might like. Both write address and write data requests show up at the same time. On the following clock the respective

*WREADYsignals are set, and then the acknowledgment takes place on the third clock where*BVALIDis set.Let’s note two things about this picture. First, the

*WREADYsignals are kept low until the request is made. This is not required of the bus and in general slows the bus down. Second, theS_AXI_BREADYsignal is held high. The particular core we are demonstrating will fail if this is not the case. We’ll come back to that in a moment. -

The second transaction illustrates one of the bounds on the write channels: Xilinx’s rules allow the write address valid signal to show up no more than two clocks before the write data. In this example, the slave holds the two

*WREADYlines low until the clock after both are valid. -

The third transaction illustrates the other bound: the write data channel may arrive up to one clock before the write address channel. As with the previous example, this slave holds the various

*WREADYlines low until both are present. The acknowledgment then takes place on the next clock. -

The final three transactions are part of a speed test measuring how fast this core can handle subsequent transactions. In the case of this slave, the slave waits until both

S_AXI_AWVALIDandS_AXI_WVALIDsignals are high before raising the ready signal. This wait period limits the speed of this slave core to one transaction every two clocks.If the Lord wills, I’d like to also present another AXI-slave core with much better throughput performance, but that will need to remain for another day.

This protocol suggests a couple formal properties.

-

Each of the

*VALIDsignals should remain high until their respective*READYsignal is also high. This applies to both the write address channel, the write data channel, as well as the acknowledgment channel. -

The data associated with each channel should be constant from when the

*VALIDsignal is set until both*VALIDand*READYare set together. -

We also discussed the two Xilinx imposed limits above as well.

– The write data channel may become active no more than one clock before the write address channel, and

– The write address channel may become active no more than two clocks before the write data channel.

-

Finally, there should be no more than one acknowledgment per write request. Well, it’s a bit more complex than that. Both write address and write data channels will need to be checked, so that there is never any write acknowledgment until a request has previously been received on both of those two channels.

Using a Formal Property Set

Further on in this article, we’ll dive into the weeds of how to express the formal properties necessary to specify an AXI-lite bus interaction. For now, I’d like to discuss what you can do with such a formal property set.

I currently have Vivado 2016.3 installed on my computer. Is it out of date? Yes. However, it works for me. Xilinx has had problems breaking things when they make updates, so I hesitate to update Vivado lest I break something that is already working.

That said, this video from Xilinx describes how to create an AXI-lite peripheral core. I followed similar instructions, and received a default demonstration AXI-lite peripheral.

I then added a formal property section to the bottom of this core.

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

//

// Formal Verification section begins here.

//

// The following code was not part of the original Xilinx demo.

//

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

`ifdef FORMALThe important part of this property section is the reference to our formal AXI-lite property file. Since the properties require some counters in order to make certain that exactly one response is given to every transaction, let’s set a width for those counters and declare them here.

localparam F_LGDEPTH = 4;

wire [(F_LGDEPTH-1):0] f_axi_awr_outstanding,

f_axi_wr_outstanding,

f_axi_rd_outstanding;For this particular design, a four bit counter is really overkill, but it will work for us.

Then, we connect the various signals associated with the AXI-lite protocol to our core. The parameters have fairly well defined meanings. The data width is the number of data bits in the bus. The address width is the number of bits required to describe a single octet in the data stream. This is different from WB, which has only the number of bits necessary to describe a word address. We’ll ignore the extra bits for now, since they are fairly irrelevant here.

//

// Connect our slave to the AXI-lite property set

//

faxil_slave #( .C_AXI_DATA_WIDTH(C_S_AXI_DATA_WIDTH),

.C_AXI_ADDR_WIDTH(C_S_AXI_ADDR_WIDTH),

.F_LGDEPTH(F_LGDEPTH)) properties(

.i_clk(S_AXI_ACLK),

.i_axi_reset_n(S_AXI_ARESETN),

//

.i_axi_awaddr(S_AXI_AWADDR),

.i_axi_awcache(4'h0),

.i_axi_awprot(S_AXI_AWPROT),

.i_axi_awvalid(S_AXI_AWVALID),

.i_axi_awready(S_AXI_AWREADY),

//

.i_axi_wdata(S_AXI_WDATA),

.i_axi_wstrb(S_AXI_WSTRB),

.i_axi_wvalid(S_AXI_WVALID),

.i_axi_wready(S_AXI_WREADY),

//

.i_axi_bresp(S_AXI_BRESP),

.i_axi_bvalid(S_AXI_BVALID),

.i_axi_bready(S_AXI_BREADY),

//

.i_axi_araddr(S_AXI_ARADDR),

.i_axi_arprot(S_AXI_ARPROT),

.i_axi_arcache(4'h0),

.i_axi_arvalid(S_AXI_ARVALID),

.i_axi_arready(S_AXI_ARREADY),

//

.i_axi_rdata(S_AXI_RDATA),

.i_axi_rresp(S_AXI_RRESP),

.i_axi_rvalid(S_AXI_RVALID),

.i_axi_rready(S_AXI_RREADY),

//

.f_axi_rd_outstanding(f_axi_rd_outstanding),

.f_axi_wr_outstanding(f_axi_wr_outstanding),

.f_axi_awr_outstanding(f_axi_awr_outstanding));If we wanted to stop here and only run a bounded model check, we could do that. However, with just a couple of more properties we can make certain this design will pass induction as well–or not, as we’ll see in a moment.

For example, a short examination of the internals of this

core

will reveal that it can only ever respond to a single transaction

request at a time. See for example the logic for

axi_awready,

and axi_wready for writes,

and similarly the logic for axi_arready for reads.

Further, once that transaction request has been made, but before the

acknowledgment has been accepted, the appropriate acknowledgment valid flag

will be high, whether bvalid or

rvalid.

Not only that, but when

the acknowledgment valid flag is high is the only time we’ll have one pending

transaction.

always @(*)

if (S_AXI_ARESETN)

begin

assert(f_axi_rd_outstanding == ((S_AXI_RVALID)? 1:0));

assert(f_axi_wr_outstanding == ((S_AXI_BVALID)? 1:0));

endLikewise, this core does not allow the number of outstanding requests on the write address channel to differ at all from those on the write data channel.

always @(*)

assert(f_axi_awr_outstanding == f_axi_wr_outstanding);Then, we create a very simple SymbiYosys script:

[tasks]

cvr

prf

[options]

cvr: mode cover

cvr: depth 60

prf: mode prove

prf: depth 40

[engines]

smtbmc

[script]

read -formal xlnxdemo.v

read -formal faxil_slave.v

prep -top xlnxdemo

[files]

xlnxdemo.v

faxil_slave.vThis script

describes

two tasks. One task,

named cvr, will check the cover properties in this core. Since we haven’t

introduced any yet, we’ll come back to this task in a moment. The second

task, prf, will attempt to

formally verify

that

this core

meets all of the

properties

required of any

AXI-lite protocol

core–basically all of the properties mentioned above.

Now, when we run SymbiYosys to check the safety properties (i.e. the assertions),

% sby -f xlnxdemo.sby prfThe proof fails almost immediately.

This first problem comes from the fact that none of the various signal registers are given appropriate initial values. While I personally consider this to be a bug, many individuals will consider this irrelevant in a core that depends upon a reset like this one does. Therefore, let’s just quietly fix the core with some initial statements and go on.

// The following lines are only questionable a bug

initial axi_arready = 1'b0;

initial axi_awready = 1'b0;

initial axi_wready = 1'b0;

initial axi_bvalid = 1'b0;

initial axi_rvalid = 1'b0;And again the design fails. This time it fails with the trace shown in Fig. 4 to the right.

|

In this image, you can see two write transactions. I’ve colored them with

two different colors, to help separate the two and make this example easier

to follow. The image differs, however,

from our previous write example in Fig 3 above simply because the

S_AXI_BREADY signal is not held high. As a result, the S_AXI_BVALID

transaction is not immediately acknowledged until S_AXI_BREADY has been

valid for a whole clock. By that time, however, the logic within the

core

has lost the reality that there is a second transaction that needs to be

acknowledged as well. Hence, once the

core

drops the S_AXI_BVALID line, a transaction has been lost.

If we want to move on and look for other problems, we could bandage over this bug with an assumption. While you’d never want to do this in production code, sometimes it is helpful to move on in order to find some other problem. In this case, a simple assumption causes this error to go away.

always @(*)

assume(S_AXI_BREADY);However, when we run the tools again the design still fails. Looking at the trace reveals that it is failing for the same basic bug again, only now the problem is found within the read channel, as shown in Fig 5.

|

If we assume that S_AXI_RREADY is always high, just like we did with

S_AXI_BREADY, this failure also vanishes and now the

core

can be

verified for all time

using

induction.

With a little looking, and a quick trace capability, it

doesn’t take long to chase down the bug. You can see the problem below

as it exists for the S_AXI_ARREADY signal. Basically, the core allowed

this signal to go high before it knew that the S_AXI_RVALID signal would

be acknowledged.

If you page through the code, you’ll find the always block, shown below,

that sets the axi_arready signal. It starts with a basic, almost

boilerplate, reset function to clear axi_arready.

always @( posedge S_AXI_ACLK )

begin

if ( S_AXI_ARESETN == 1'b0 )

begin

axi_arready <= 1'b0;

axi_araddr <= 7'b0;

end

else

beginEarly on in the operation, though, we find the bug. In particular,

axi_arready is set irrespective of whether the result channel is stalled

and there’s no place to hold the result.

if (~axi_arready && S_AXI_ARVALID)

begin

// indicates that the slave has acceped the valid read address

axi_arready <= 1'b1;

// Read address latching

axi_araddr <= S_AXI_ARADDR;

end

else

begin

axi_arready <= 1'b0;

end

end

endJust a touch of extra logic will fix this for us.

if (!axi_arready && S_AXI_ARVALID && (!S_AXI_RVALID || S_AXI_RREADY))

begin

// indicates that the slave has acceped the valid read address

axi_arready <= 1'b1;

// Read address latching

axi_araddr <= S_AXI_ARADDR;

end

else

begin

axi_arready <= 1'b0;

end

end

endA similar fix to the write channel and the design should pass nicely.

Cover

The check above encourages us that this design will not violate any of our

safety properties, but will it work? Or, rather, how well can it be made

to work? To answer that question, let’s create a cover() property.

Cover properties are known as liveness properties, versus the assertion

properties which are known as safety properties. When a safety property

fails, a trace is created showing how the property may be made to fail.

However, when a safety property succeeds you know the assert() will always

be valid and so no trace is created. Cover properties are the opposite. A

cover property succeeds if there is at least one way to make the statement

true. In that case, a trace is generated. More generally, one trace is

generated for every cover() statement within a design, or the cover()

check will fail.

Within the formal property set, there are two cover properties just to make certain the design is able to function. These properties verify that both a read and write operation are able to succeed using the core.

What I want to do now is to check performance, and we can use a cover property for that purpose.

Let’s see if we can retire four write instructions in four clocks.

always @(posedge S_AXI_ACLK)

cover( ((S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY))

&&($past((S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY),1))

&&($past((S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY),2))

&&($past((S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY),3)));Let’s also test whether we can retire four read requests in four clocks as well.

always @(posedge S_AXI_ACLK)

cover( ((S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY))

&&($past((S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY),1))

&&($past((S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY),2))

&&($past((S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY),3)));These two tests would be easier to express with concurrent assertions, such as:

// Writes

cover property (@(posedge i_clk)

(S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY) [*4]);

// Reads

cover property (@(posedge i_clk)

(S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY) [*4]);Wow, those are nice to work with!

I personally like the four clock test, because sometimes there is a single stage within the design somewhere that can queue up an answer and so succeed on a two clock test. A four clock test on a design this simple will only succeed if the core can truly retire one instruction on every clock.

Not surprisingly, this test fails. This particular core is unable to handle a one transaction per clock throughput.

If high speed were your goal, then, you would say the core is crippled. (Yes, I have an alternative core if you want something that uses AXI-lite and yet has better performance.)

We could adjust the two tests and make them check for one instruction retiring on every other clock.

// First a write check

always @(posedge S_AXI_ACLK)

cover( ((S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY))

&&($past((S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY),2))

&&($past((S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY),4))

&&($past((S_AXI_BVALID)&&(S_AXI_BREADY),6)));

// Now a read check

always @(posedge S_AXI_ACLK)

cover( ((S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY))

&&($past((S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY),2))

&&($past((S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY),4))

&&($past((S_AXI_RVALID)&&(S_AXI_RREADY),6)));This test now succeeds.

If you choose to examine the formal properties within the core, you’ll notice there is also a very large set of code at the bottom to set up two rather complicated cover traces. We’ve already reviewed the results of those complex cover statements in Figs. 2 and 3 above.

Exhaustive Coverage, Exponential Complexity

The first lesson of formal verification is that it is exhaustive. Every possible input, output, and register combination are checked to determine whether a property holds or not. As you might imagine, this creates an exponential explosion in complexity that can be hard to manage. This can often discourage a learner from trying formal methods in the first place.

To put that whole argument into perspective, know this: I have a series of not one or two but twelve separate AXI-lite proofs in my Wishbone to AXI bridge(s) repository. It takes me less than two minutes to formally verify all of these cores.

Finally, consider what we’ve done: for the price of a small insertion of code into our design, referencing a pre-written property set, and for the cost of only a handful of other core-specific properties, we’ve managed to find, fix, and then formally verify an AXI-lite core. After you’ve done this once or twice, you’ll find that the whole verification process takes only minutes to set up, and less than that to get your first trace. This makes it very easy for me, when I want to reply to someone’s request for help on either Xilinx’s or Digilent’s forums, to quickly review their code and provide a comment on it.

Fixing the code? Well, that can take more time.

So just what does this property set look like?

AXI-lite Properties

We’ve already discussed most of the properties above, all that remains now is to lay out the details and write the immediate assertions to accomplish these tasks. The basic properties were:

-

Requests must wait to be accepted

-

Acknowledgments can only follow requests

-

All responses must return in a known number of cycles

-

Waiting requests should not be held waiting more than some maximum delay

The first step in writing this property set will be to create several configuration parameters that can be used to configure the properties to match the needs of our design. Shown below is the AXI-lite slave property set, and the various configuration parameters within it.

The first configuration parameter is the width of the bus.

module faxil_slave #(

// The width of the data bus

parameter C_AXI_DATA_WIDTH = 32,// Fixed, width of the AXI R&W dataWhile most of my work is done with a 32-bit bus, the property set should be generic enough to allow bus widths of other sizes, such as 8, 16, 64, or 128 bits. Why might you want 128 bits? Because many designs including DDR SDRAM’s can transfer 128-bits or more per clock.

Following the number of data bits, C_AXI_ADDR_WIDTH controls the number

of bits used to describe an address within the peripheral. This needs to be

a sufficient number of bits necessary to access every octet within the address

space of the slave, even though we are going to ignore the sub-word address

bits for now. (There’s only one requirement of them, associated with the

S_AXI_WSTRB signal, and I haven’t coded that up yet.)

parameter C_AXI_ADDR_WIDTH = 28,// AXI Address width (log wordsize)Further, since I find C_AXI_DATA_WIDTH and C_AXI_ADDR_WIDTH rather

cumbersome to type, I’m going to create two short-cut names: DW for the

data bus width, and AW for the address width.

localparam DW = C_AXI_DATA_WIDTH,

localparam AW = C_AXI_ADDR_WIDTH,Some implementations add

AXI

cache flags to the address request.

These flags indicate whether the transaction is to be bufferable,

non-bufferable, cachable, non-cachable, or more. I’m not personally using

these flags. However, to handle both cores with and without these bits,

we’ll use the parameter F_OPT_HAS_CACHE. If F_OPT_HAS_CACHE is set,

the slave will assume particular values for i_axi_awcache

and i_axi_arcache, indicating

that the write is to be done to the cache or through the cache. This is

probably more important for an

AXI

master than the slave, but since the two are mirrors of each other, we’ll

keep it in here.

parameter [0:0] F_OPT_HAS_CACHE = 1'b0,Sometimes I need to verify a write-only

AXI interface, such as in this AXI-lite

write-channel to wishbone

bridge. In

that case, I’ll want to assume the read channel is idle and remove the read

channel cover check. F_OPT_NO_READS can be set to make this happen.

parameter [0:0] F_OPT_NO_READS = 1'b0,F_OPT_NO_WRITES is the analog to F_OPT_NO_READS. If

F_OPT_NO_WRITES is set, then the proof will assume the write channel

is idle, and remove the write channel cover check. This is used by my

AXI-lite read-channel to wishbone

bridge core.

parameter [0:0] F_OPT_NO_WRITES = 1'b0,AXI

defines three separate possible responses: an OK response,

a slave produced an error response, or an interconnect produced

an error response. If a particular slave cannot produce any

form of

bus error,

it makes sense to disallow it. Clearing

F_OPT_BRESP to zero will disallow any form of

error on the write channel.

parameter [0:0] F_OPT_BRESP = 1'b1,

//

// The same is true for F_OPT_RRESP for the read channel

parameter [0:0] F_OPT_RRESP = 1'b1,Xilinx’s AXI reference

guide

requires a rather lengthy reset of 16 clock periods. If the slave

(or master) being verified isn’t creating that reset, then it makes sense

to just assume the reset is present. The F_OPT_ASSUME_RESET configures

the core to do just that.

parameter [0:0] F_OPT_ASSUME_RESET = 1'b1,In order to insure that there is only one acknowledgment for every

request received, we’ll need to count requests and acknowledgments

and compare our signals to these counters. F_LGDEPTH specifies

the number of bits to be used for those counters.

parameter F_LGDEPTH = 4,We’re going to insist that no transaction remains stalled for more

than some maximum number of clock cycles, F_AXI_MAXWAIT. This also

keeps the design and traces moving during our proof. While the constraint

placed upon the design as a result is somewhat artificial, you can adjust

it to match what you would expect within your design environment.

parameter [(F_LGDEPTH-1):0] F_AXI_MAXWAIT = 12,Our last parameter, F_AXI_MAXDELAY, is used to make certain that,

following a request, the result will be returned to the

AXI bus

master within a given number of clock cycles. The number of cycles to wait

is very implementation dependent, so it needs to be a configuration parameter.

We set it here.

parameter [(F_LGDEPTH-1):0] F_AXI_MAXDELAY = 12

) (In many ways, F_AXI_MAXDELAY=12 is overkill for the demonstration designs

in the wishbone to AXI bridge repository

we are taking our examples from.

However, other designs

have needed delays of 65 clocks or more, so this is an appropriate

configuration parameter.

Let me add one other note on these two clock durations: the shorter

F_AXI_MAXWAIT and F_AXI_MAXDELAY are, the faster your proof will complete.

Let’s now move on from the parameters within the formal property

file

to the inputs and outputs of the

module

itself. Since this formal property

set

is my own code rather than Xilinx’s,

I’m also going to switch notations to one I am familiar with. Inputs

to any core in my notation start with i_, outputs begin with an o_.

Further, only constant values such as parameter or macros will use all

capitals. Finally, since the core we will be writing is a formal property

set,

all of the interface wires will be inputs.

input wire i_clk, // System clock

input wire i_axi_reset_n,

// AXI write address channel signals

input wire i_axi_awready,//Slave is ready to accept

input wire [AW-1:0] i_axi_awaddr, // Write address

input wire [3:0] i_axi_awcache, // Write Cache type

input wire [2:0] i_axi_awprot, // Write Protection type

input wire i_axi_awvalid, // Write address valid

// AXI write data channel signals

input wire i_axi_wready, // Write data ready

input wire [DW-1:0] i_axi_wdata, // Write data

input wire [DW/8-1:0] i_axi_wstrb, // Write strobes

input wire i_axi_wvalid, // Write valid

// AXI write response channel signals

input wire [1:0] i_axi_bresp, // Write response

input wire i_axi_bvalid, // Write reponse valid

input wire i_axi_bready, // Response ready

// AXI read address channel signals

input wire i_axi_arready, // Read address ready

input wire [AW-1:0] i_axi_araddr, // Read address

input wire [3:0] i_axi_arcache, // Read Cache type

input wire [2:0] i_axi_arprot, // Read Protection type

input wire i_axi_arvalid, // Read address valid

// AXI read data channel signals

input wire [1:0] i_axi_rresp, // Read response

input wire i_axi_rvalid, // Read reponse valid

input wire [DW-1:0] i_axi_rdata, // Read data

input wire i_axi_rready, // Read Response readyWell, almost. We’re also going to create three outputs, as shown below, so that assertions may be connected to our various counters to constrain them to the implementation using them. Such constraints are necessary in order to pass induction, as we’ve discussed before.

//

output reg [(F_LGDEPTH-1):0] f_axi_rd_outstanding,

output reg [(F_LGDEPTH-1):0] f_axi_wr_outstanding,

output reg [(F_LGDEPTH-1):0] f_axi_awr_outstanding

);Since checking for transactions can be somewhat tedious below, I’ll declare

some simple transaction abbreviations here. These are basically abbreviations

for when both *VALID and *READY are true indicating that either a

transaction or or an acknowledgment

handshake

completes.

// wire w_fifo_full;

wire axi_rd_ack, axi_wr_ack, axi_ard_req, axi_awr_req, axi_wr_req;

//

assign axi_ard_req = (i_axi_arvalid)&&(i_axi_arready);

assign axi_awr_req = (i_axi_awvalid)&&(i_axi_awready);

assign axi_wr_req = (i_axi_wvalid )&&(i_axi_wready);

//

assign axi_rd_ack = (i_axi_rvalid)&&(i_axi_rready);

assign axi_wr_ack = (i_axi_bvalid)&&(i_axi_bready);I’m also trying something new with this property set. Since bus slave

properties are very similar to those for the master, save only that the

assumptions and assertions are swapped, I’m going to create two macros:

SLAVE_ASSUME and SLAVE_ASSERT. These are defined from the perspective of

the slave to be assume and assert respectively. Within the master,

these definitions will naturally swap.

`define SLAVE_ASSUME assume

`define SLAVE_ASSERT assertUsing a macro like this makes it easier to run

meld

on both

slave

and

master

property files when making updates. This way the actual logic differences

stand out more. Interested in seeing how well this works? Just install

meld, download the

wb2axip repository, then cd into

the bench/formal

directory and run

% meld faxil_slave.v faxil_master.vto see how easy it is to spot differences between the two cores.

Reset Properties

I’ve struggled a bit with the reset properties for

AXI.

Specifically, what

core

is it that actually creates the reset that needs to be verified here?

That core should have the

assertions

applied to it. However, the reset is often defined by some other module

within the design. Hence, we’ll either

assert or assume the reset is initially set based instead on the

F_OPT_ASSUME_RESET parameter from above.

generate if (F_OPT_ASSUME_RESET)

begin : ASSUME_INIITAL_RESET

always @(*)

if (!f_past_valid)

assume(!i_axi_reset_n);

end else begin : ASSERT_INIITAL_RESET

always @(*)

if (!f_past_valid)

assert(!i_axi_reset_n);

end endgenerateXilinx requires that the AXI reset be asserted for a minimum of 16 clock cycles. Our first step is to count the number of cycles the reset signal is active.

initial f_reset_length = 0;

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (i_axi_reset_n)

// If ever the reset is released, "reset" the reset-length

// counter back to zero.

//

f_reset_length <= 0;

else if (!(&f_reset_length))

// Otherwise, just quietly increment the counter until we get

// to 15

f_reset_length <= f_reset_length + 1'b1;We can then make (assumptions) or assertions about the reset signal to make certain it is held long enough.

generate if (F_OPT_ASSUME_RESET)

begin : ASSUME_RESET

// ...

end else begin : ASSERT_RESET

always @(posedge i_clk)

if ((f_past_valid)&&(!$past(i_axi_reset_n))&&(!$past(&f_reset_length)))

assert(!i_axi_reset_n);

always @(*)

if ((f_reset_length > 0)&&(f_reset_length < 4'hf))

assert(!i_axi_reset_n);

end endgenerateFinally, now that we know our design meets its reset requirements, we can

create some properties regarding what must happen as a result of a reset.

Specifically, we’ll require that following any reset, the various *VALID

flags should be set to zero.

We’re also going to apply this to the very first clock cycle of the design, by

also checking for !f_past_valid and by applying these properties through

initial statements. As you may recall, this was the issue

the Xilinx core

had above with its (missing) initial statements.

// Nothing should be returned or requested on the first clock

initial `SLAVE_ASSUME(!i_axi_arvalid);

initial `SLAVE_ASSUME(!i_axi_awvalid);

initial `SLAVE_ASSUME(!i_axi_wvalid);

//

initial `SLAVE_ASSERT(!i_axi_bvalid);

initial `SLAVE_ASSERT(!i_axi_rvalid);

// Same thing, but following any reset as well

always @(posedge i_clk)

if ((!f_past_valid)||(!$past(i_axi_reset_n)))

begin

`SLAVE_ASSUME(!i_axi_arvalid);

`SLAVE_ASSUME(!i_axi_awvalid);

`SLAVE_ASSUME(!i_axi_wvalid);

//

`SLAVE_ASSERT(!i_axi_bvalid);

`SLAVE_ASSERT(!i_axi_rvalid);

endMoving on to the response signals, S_AXI_BRESP for the write channel and

S_AXI_RRESP for the read channel, we’ll note that the 2'b01 pattern is

the only pattern disallowed by the AXI

specification.

always @(*)

if (i_axi_bvalid)

`SLAVE_ASSERT(i_axi_bresp != 2'b01); // Exclusive access not allowed

always @(*)

if (i_axi_rvalid)

`SLAVE_ASSERT(i_axi_rresp != 2'b01); // Exclusive access not allowedStability Properties

The rule we discussed above was that the signals that are coupled with any transaction should be held constant as long as the transaction remains outstanding (i.e. valid but not ready). This is a basic handshake that we also required when building our WB properties. Let’s capture that handshake property here in this context.

Simply put using concurrent assertions, we could express this as:

`SLAVE_ASSUME property (@(posedge i_clk)

disable iff (!i_axi_reset_n)

(i_axi_awvalid && !i_axi_awready)

|=> i_axi_awvalid && ($stable(i_axi_awaddr)));

`SLAVE_ASSUME property (@(posedge i_clk)

disable iff (!i_axi_reset_n)

(i_axi_wvalid && !i_axi_wready)

|=> i_axi_wvalid && $stable(i_axi_wdata)

&& $stable(i_axi_wstrb) );

`SLAVE_ASSERT property (@(posedge i_clk)

disable iff (!i_axi_reset_n)

(i_axi_bvalid && !i_axi_bready)

|=> i_axi_bvalid && $stable(i_axi_bresp));

// ...Alternately, in order to use the immediate assertions supported by the free version of SymbiYosys, we’ll need to put a little more work into this. First, we want to avoid the first clock period and any clock period following a reset. This is to make sure our properties deal with valid data.

always @(posedge i_clk)

if ((f_past_valid)&&($past(i_axi_reset_n)))

beginNow, for each channel, we’ll write out the properties in question. Basically

if the *VALID was true on the previous cycle but the *READY was false,

then the *VALID should remain true and the associated data should be stable.

For the write address channel, the first of five, this property looks like the following.

// Write address channel

if ((f_past_valid)&&($past(i_axi_awvalid))&&(!$past(i_axi_awready)))

begin

`SLAVE_ASSUME(i_axi_awvalid);

`SLAVE_ASSUME($stable(i_axi_awaddr));

end

// Apply to all other incoming channels

endThe other channel properties are nearly identical, so we’ll skip them for brevity here. The important part to remember is that we will assume properties of the input, and assert properties of our local state and any outputs. Hence, in this case we’ll assume the properties of the write address channel, the write data channel, and the read address channel, but assert properties of the two acknowledgment channels.

Maximum Delay

We said above that no channel should remain stalled for more than a finite

number of clock cycles. Such a stall would be defined as *VALID && !*READY.

Let’s check that property for each channel here, but only if we were given

an F_AXI_MAXWAIT value greater than zero.

generate if (F_AXI_MAXWAIT > 0)

begin : CHECK_STALL_COUNT

//

//

reg [(F_LGDEPTH-1):0] f_axi_awstall,

f_axi_wstall,

f_axi_arstall,

f_axi_bstall,

f_axi_rstall;To create a check constraining how many clock cycles a design may be allowed to stall a channel, we’re going to have to first count the number of stalls.

I’ll show the write address channel stall count here, and skip the others for brevity again.

I should also mention, it took me several rounds to get this count just right. So, here’s the basic logic:

- Anytime we either reset the core, or anytime there’s no pending write request, or the write address request is accepted, the write address bus isn’t stalled and we set the counter back to zero. This much was straightforward, and matches my first draft.

initial f_axi_awstall = 0;

always @(posedge i_clk)

if ((!i_axi_reset_n)||(!i_axi_awvalid)||(i_axi_awready))

f_axi_awstall <= 0;- Likewise any time we are waiting for the other write channel, in this case the write data channel, to request a transaction we also set the counter to zero. This allows the Xilinx AXI-lite demo code to stall the bus as long as it wants while waiting for the other channel to synchronize.

else if ((f_axi_awr_outstanding >= f_axi_wr_outstanding)

&&(i_axi_awvalid && !i_axi_wvalid))

// If we are waiting for the write channel to be valid

// then don't count stalls

f_axi_awstall <= 0;- Here’s the part that caught me by surprise though: we only want to accumulate stalls on this request channel if the back end isn’t stalled. Hence if there’s no waiting acknowledgment, or likewise if the acknowledgment that is waiting has just been accepted, then and only then do we count a stall against the write address channel for not being ready.

else if ((!i_axi_bvalid)||(i_axi_bready))

f_axi_awstall <= f_axi_awstall + 1'b1;- Finally, assert that the number of stalls is within our limit.

always @(*)

`SLAVE_ASSERT(f_axi_awstall < F_AXI_MAXWAIT);

// The other channel stall counts are very similarWhy would we assert this? Because the stall signal, S_AXI_AWREADY, is

an output of the slave core, and we always place assertions on outputs and

assumptions on inputs.

Hence, if you look down through the property

file

a bit further, you’ll see an assumption made for the read acknowledgment

channel. Why is this an assumption? Because it is dependent upon the

S_AXI_BREADY input to the core.

always @(*)

`SLAVE_ASSUME(f_axi_rstall < F_AXI_MAXWAIT);

end endgenerateOf course, all of these assumptions will swap with their assertion counterparts when we go to the AXI-lite master property set.

Xilinx Constraints

Remember the two Xilinx constraints? The additional rules to make things work? Here they are written out.

-

The address line will never be more than two clocks ahead of the write data channel, and

-

The write data channel will never be more than one clock ahead of the address channel.

I found these rules in a DDR3 IP core module usage guide, though I can’t seem to find that guide right now. However, since they’ve helped make the various proofs complete, I’ve chosen to include these rules here.

Let’s express these as formal properties. First, if there was a write address request two clocks ago, and no intervening write data request, then we want to assume a write data request now.

Ok, not quite, that’s missing a key detail: it is possible that the write address request of two clocks ago followed a write data request. That means we’ll also have to check that the number of write data and write address requests were equal two clocks ago, or there had been more write address requests.

This is another one of those properties where a concurrent assertion would make the most sense,

`SLAVE_ASSUME property (@(posedge i_clk)

disable iff (!i_axi_reset_n)

(i_axi_awvalid && !i_axi_wvalid)

&&(f_axi_awr_outstanding>=f_axi_wr_outstanding)

##1 (!i_axi_wvalid)

|=> i_axi_wvalid);We could also express this same property as an immediate assertion. It’s uglier and harder to read, but it still works well.

always @(posedge i_clk)

if ((i_axi_reset_n)&&($past(i_axi_reset_n))

&&($past(i_axi_awvalid && !i_axi_wvalid,2))

&&($past(f_axi_awr_outstanding>=f_axi_wr_outstanding,2))

&&(!$past(i_axi_wvalid)))

`SLAVE_ASSUME(i_axi_wvalid);The second rule is simpler since it only covers two clock periods instead of three. It’s the same basic thing, just with the channels reversed and one less clock period.

always @(posedge i_clk)

if ((i_axi_reset_n)&&(!$past(i_axi_awvalid))&&($past(i_axi_wvalid))

&&(f_axi_awr_outstanding < f_axi_wr_outstanding))

`SLAVE_ASSUME(i_axi_awvalid);Together these two properties will keep the two channels roughly synchronized with one another. Making the actual synchronization work within the peripheral code will still remain a challenge.

Compare the number of acknowledgments to requests

The next rule we want to check is that for every acknowledgment, there must have been one and only one request.

No matter how we do this, we’ll need to start by counting the number of outstanding requests. This count goes as follows: following any reset, the number of outstanding requests must be zero.

initial f_axi_awr_outstanding = 0;

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (!i_axi_reset_n)

f_axi_awr_outstanding <= 0;Likewise anytime we have accepted a request, or had an acknowledgment on the return channel accepted, but not both, the count will adjust.

else case({ (axi_awr_req), (axi_wr_ack) })

2'b10: f_axi_awr_outstanding <= f_axi_awr_outstanding + 1'b1;

2'b01: f_axi_awr_outstanding <= f_axi_awr_outstanding - 1'b1;

default: begin end

endcasePlease notice that I didn’t use a pair of if statements here, such as

if there’s been a write address channel request then increment the counter,

else if there’s been a write response then decrement the counter. I’ve tried

that approach several times in the past, but I always seem to get burned

by it. Why? Because of the cases the if statements don’t cover, usually

the case where there’s both a request and an acknowledgment on the same clock

cycle.

Two other counters, f_axi_wr_outstanding based upon the write data channel

and f_axi_rd_outstanding based upon the read channel, are defined similarly.

We can now start creating some properties using these count values. First, we want to make certain our counters never overflow.

always @(posedge i_clk)

`SLAVE_ASSERT(f_axi_wr_outstanding < {(F_LGDEPTH){1'b1}});

always @(posedge i_clk)

`SLAVE_ASSERT(f_axi_awr_outstanding < {(F_LGDEPTH){1'b1}});

always @(posedge i_clk)

`SLAVE_ASSERT(f_axi_rd_outstanding < {(F_LGDEPTH){1'b1}});Second, in order to guarantee that the counters never overflow, we’ll need to insist that the channel stops making a request one clock earlier.

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (f_axi_awr_outstanding == { {(F_LGDEPTH-1){1'b1}}, 1'b0} )

assert(!i_axi_awvalid);

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (f_axi_wr_outstanding == { {(F_LGDEPTH-1){1'b1}}, 1'b0} )

assert(!i_axi_wvalid);

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (f_axi_rd_outstanding == { {(F_LGDEPTH-1){1'b1}}, 1'b0} )

assert(!i_axi_arvalid);You might notice that these are all a series of assertions–for both

master

and

slave.

They are not SLAVE_ASSERT()ions, but rather regular assertions.

This somewhat violates our

rule, that we only make assertions of local state and outputs. However,

if an assumption is required to keep this number lower, that assumption

should really exist within the implementation defined code. Hence we’ll just

use regular assertions here.

Finally, to make certain that acknowledgments do follow requests, we can make a couple of assertions. The three counters above make these assertions really easy.

First, on any write acknowledgment, there must be at least one outstanding write address request that needs to be acknowledged. Likewise, there also needs to be one write data request that needs to be acknowledged.

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (i_axi_bvalid)

begin

`SLAVE_ASSERT(f_axi_awr_outstanding > 0);

`SLAVE_ASSERT(f_axi_wr_outstanding > 0);

endNotice here that I’m applying the test every time i_axi_bvalid is true,

not every time axi_wr_ack, axi_awr_ack, nor every time

S_AXI_BVALID && S_AXI_BREADY. In other words, before even attempting

an acknowledgment, the respective counter should be greater than one.

A second thing to notice is that I’m not excepting the case where a request is being made on the same cycle. Such an acknowledgment, dependent only on a combinatorial expression of the inputs, is specifically disallowed by the AXI specification.

The assertion for the read channel is nearly identical to those for the write channel above.

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (i_axi_rvalid)

`SLAVE_ASSERT(f_axi_rd_outstanding > 0);This guarantees we’ll never respond to the bus unless a prior request has been made.

We haven’t yet guaranteed that every request will get a response. For that, we need to count the number of clock cycles following a request to when a response should taken place.

Maximum Response Delay Check

The maximum response delay check is just that: checking that every request

gets a response within a maximum number of clock periods. This number of clock

periods is captured by the configuration parameter F_AXI_MAXDELAY. Setting

this parameter to zero will disable this check.

As with the other tests, we’ll start by counting how long a request remains unacknowledged or outstanding.

generate if (F_AXI_MAXDELAY > 0)

begin : CHECK_MAX_DELAY

reg [(F_LGDEPTH-1):0] f_axi_wr_ack_delay,

f_axi_rd_ack_delay;This count is very similar to the stall count above. We’ll examine the read portion below, although the write count portion is similar. For a read, we’ll only count up if the reset is inactive, no acknowledgment is pending, and there exists an outstanding read that has not been acknowledged.

initial f_axi_rd_ack_delay = 0;

always @(posedge i_clk)

if ((!i_axi_reset_n)||(i_axi_rvalid)||(f_axi_rd_outstanding==0))

f_axi_rd_ack_delay <= 0;

else

f_axi_rd_ack_delay <= f_axi_rd_ack_delay + 1'b1;

// ...We can then assert that the counter must remain less than the maximum acknowledgment delay.

always @(*)

`SLAVE_ASSERT(f_axi_rd_ack_delay < F_AXI_MAXDELAY);

// ...

end endgenerateThat’s the last of the safety properties necessary to determine that a core abides by the rules of AXI-lite.

When I originally started working with formal

verification, I would

stop once I’d finished writing my assertions and assumptions.

I’ve since been burned multiply times by believing that a core worked when I’d

somehow missed something internally, or perhaps assumed one property too many.

For that reason, let’s add in some cover() properties.

Cover Properties

As a final property category, it’s important to have some assurance that a given AXI-lite slave core can handle a write request,

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (!F_OPT_NO_WRITES)

cover((i_axi_bvalid)&&(i_axi_bready));and a read request.

always @(posedge i_clk)

if (!F_OPT_NO_READS)

cover((i_axi_rvalid)&&(i_axi_rready));

endmoduleNow, upon any SymbiYosys run in cover mode, the formal solver will find some path from reset, through either read or write request, through whatever operation the slave needs to do within its implementation, all the way to the acknowledgment being accepted. In many cases, this will also showcase the logic within the slave, giving you a trace you can use when debugging so that you can make sure you are implementing your logic properly.

Conclusion

I’d like to say that it only took me one weekend to build these properties. That’s roughly true. Interface property lists such as this one really aren’t that hard or difficult to build for a given application. Even better, the basic properties tend to remain the same from one application to the next. For example, we’re still using the same basic handshake properties here that we used for the WB bus, only now we are using different names for the signals.

However, it has taken some work on my part to build some example bus bridges and a demonstration AXI-lite slave core to give this property list some good exercise. Further, I’ve been using these properties to check the functionality of other AXI-slaves that I’ve found on-line, so I have some decent confidence that these properties work.

As we’ve seen above, these properties can be used to diagnose and then fix any AXI-lite core, such as the one produced by Vivado that we discussed above.

Even better, I’ve been able to use these properties to create a core that outperforms Xilinx’s AXI-lite demonstration core. This new example core can handle one read or write transaction request and thus acknowledgment on every clock, and it can keep this speed up indefinitely. Now, if only the interconnect would maintain that speed, you’d have a peripheral that runs a full twice as fast.

Just to give you a hint for what this core might do, here’s an example write trace from this new core.

|

|

Here’s an example read trace in Fig. 7 on the right.

Want to know how to build an AXI-lite core with this kind of throughput? Check out the buffered handshake approach to pipeline signaling and then stay tuned. That will likely be my next post on the topic of AXI-lite.

But what about the full AXI protocol? While I have a full Wishbone to full AXI bridge, I have yet to build a property file that would describe the full AXI protocol properly. Worse, I’ve put a lot of time into trying to build such a file. Too much time, in fact, so I really can’t afford to put much more time into it.

I’m sure I’ll get it soon enough, but given the amount of work it has taken me so far, it’s not very likely to be an open source core in the near future.

These bugs were reported to Xilinx on 28 Dec, 2018. As of Jan, 2020, they have not yet been fixed.

And it came to pass, when the king had heard the words of the book of the law, that he rent his clothes. (2Kings 22:11)